Extreme Weather and Transit Rail: Managing Track Risk, Resilience and Reliability

Extreme weather is no longer an occasional disruption for rail transit systems. It has become a persistent operational challenge. Heat waves, cold polar snaps, intense rainfall, flooding and wind-driven storms are occurring more frequently and with greater intensity, stressing rail infrastructure and operations in ways that were not fully anticipated when many systems were designed.

For transit agencies, the consequences extend well beyond asset degradation. Service reliability, safety, inspection effectiveness and recovery time are increasingly shaped by weather-driven risks. Addressing these challenges requires more than isolated fixes. It demands a combination of adapted procedures, targeted infrastructure investments and improved monitoring technologies that allow agencies to anticipate problems before they disrupt service.

Extreme weather affects rail transit infrastructure, particularly track and power systems, requiring agencies to adapt their strategies to improve resilience and reliability.

Thermal extremes and the growing challenge of rail stress

Among the most persistent weather-related challenges facing rail transit systems are temperature extremes. High temperatures increase the risk of track buckling, while extreme cold raises the likelihood of rail breaks. Historically, agencies treated these risks as seasonal and largely predictable. Today, overlapping temperature extremes—such as late-winter cold followed by early spring heat—are making thermal stress management more complex and less predictable.

Continuous welded rail, now standard across most transit systems, is especially sensitive to temperature changes. As rail temperature deviates from its rail neutral temperature (RNT), internal longitudinal forces build within the rail. If those forces exceed the restraining capacity of fasteners, crossties and ballast, then track geometry can be compromised.

In hot conditions, this can result in lateral track buckles that require immediate slow orders or service suspensions. In cold weather, tensile stresses can lead to sudden rail fractures. Both scenarios present significant safety risks and demand rapid operational response.

To manage these risks, agencies rely on a combination of established practices, including maintaining appropriate RNT through rail adjustment, scheduling temperature-based inspections and issuing slow orders when thresholds are exceeded. Increasingly, rail temperature prediction models are being used to support these decisions. Unlike ambient air temperature, which often underestimates rail temperature, these models account for factors such as solar radiation, wind speeds and rail material properties to provide more accurate forecasts of actual rail conditions.

More advanced modeling tools are also being used to support risk-based decision-making. By evaluating lateral track strength and local track conditions, agencies can establish temperature thresholds that better reflect real-world buckling risk rather than relying solely on conservative, system-wide limits. These approaches allow for more targeted inspections and operational responses while maintaining safety.

Effective thermal stress management also depends on proper rail adjustment and de-stressing practices. Modern software tools help agencies calculate appropriate adjustment parameters based on measured conditions and visualize resulting RNT profiles. This supports more consistent restoration of neutral temperature and reduces the likelihood of unintended stress concentrations following maintenance activities.

Track support conditions: Where weather effects compound

Thermal stress does not act in isolation. Track stiffness and support conditions play a critical role in how rail responds to temperature changes, and these conditions are often heavily influenced by weather.

In cold climates, frozen ballast, particularly in areas with poor drainage, can create overly stiff track that limits the rail’s ability to redistribute stress, increasing the likelihood of rail breaks. Conversely, during wet weather or rapid thawing, soft track areas such as mud spots can develop due to saturated subgrade and inadequate drainage. These conditions lead to ballast pumping, reduced lateral resistance and increased susceptibility to buckling during warm weather.

What makes these issues particularly challenging is their compounding nature. Poor drainage accelerates track degradation. Degraded track amplifies the effects of thermal stress.

Thermal stress, in turn, increases maintenance demands during periods when work windows are already constrained by weather. As precipitation events become more intense, agencies are placing renewed emphasis on drainage improvements, ballast condition monitoring and identifying stiffness transitions that may not have posed problems under historical climate patterns.

Winter operations: Visibility, power and inspection challenges

Cold-weather operations present a distinct set of challenges, particularly in regions that experience heavy snow and ice. Switches and turnouts are among the most vulnerable assets. Packed snow and ice can prevent switch points from closing fully, leading to failures that disrupt service and require manual intervention. While switch heaters, snow melters and hot air blowers are widely used to mitigate these risks, they are not always practical at every location due to power availability, cost or maintenance requirements.

For electrified systems, third-rail icing presents another major risk. Ice accumulation can interrupt power collection, resulting in stalled trains and cascading service delays. Protective covers and de-icing trains can reduce exposure, but early detection and inspection remain critical to preventing service impacts.

Winter conditions also complicate track inspection itself. Snow and ice can obscure surface defects, making traditional visual inspections less effective. To address this limitation, many agencies rely on vehicle-based inspection methods that can identify issues even when components are partially hidden, such as vehicle track interaction (VTI) monitors or gage restrain measurement systems. Because these systems measure the dynamic response of vehicles rather than relying solely on visual cues, they remain effective in conditions where visibility is limited. Further, these same tools often provide additional benefits year-round, including the detection of mud pumping, fastener issues and switch condition problems that may worsen during wet or freeze-thaw cycles.

Using vehicle response to understand track condition

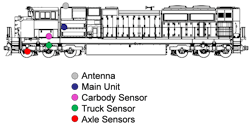

Vehicle/track interaction (V/TI) monitoring offers particular advantages during extreme weather. Because it relies on accelerometer-based measurements rather than optical systems, its effectiveness is not limited by snow, ice, standing water or poor visibility. Installed on revenue-service vehicles, VTI systems measure vertical and lateral vehicle responses that reflect underlying track and support conditions. Over time, these measurements help agencies identify weather-related maintenance issues that are often difficult to observe directly.

From proven operational experience, these measurements support identifying specific infrastructure condition issues. Carbody vertical responses are commonly linked to profile irregularities and mud pumping. Axle vertical impacts often indicate rail surface defects or rail breaks associated with thermal fatigue and freeze–thaw cycles. Mid-chord offset measurements are effective at identifying substructure heaving, ballast loss and soft support conditions related to poor drainage or flooding.

Because this data is collected continuously during normal in-service operations, it complements scheduled inspections by providing ongoing awareness between inspection cycles. Detected anomalies are automatically processed, assigned severity levels and referenced to precise track locations, allowing maintenance teams to focus on field inspections where risk is highest.

In extreme weather conditions, this capability supports earlier identification of developing problems, particularly in areas where repeated exposure to moisture, freezing or inadequate drainage accelerates deterioration. Over time, recurring low-level responses can highlight locations experiencing chronic stress, helping agencies prioritize corrective actions before conditions escalate into service-impacting failures.

By maintaining measurement capability when traditional inspections are constrained, VTI monitoring strengthens agencies’ ability to manage weather-driven risks and maintain safe, reliable transit operations.

Acute weather events and system-wide impacts

While thermal effects are persistent, acute extreme weather events often cause the most dramatic disruptions. Flooding, storm surge and intense rainfall can overwhelm drainage systems, leading to:

- Track washouts

- Submerged signal houses

- Damaged cable routes and power equipment

Coastal and low-lying systems are particularly vulnerable to storm surge, while inland systems increasingly face flash flooding that was once considered rare.

High winds associated with hurricanes, severe thunderstorms and other major storms can damage overhead contact systems, topple trees onto tracks and scatter debris across the right-of-way. These events often affect large geographic areas simultaneously, complicating response and recovery efforts.

In cut and embankment territory, heavy rainfall can trigger landslides and mudslides that undermine track support. These failures may not be immediately visible, underscoring the need for monitoring systems that can detect changes before a derailment risk develops.

Adapting strategies for a changing climate

As weather extremes become more frequent, transit agencies recognize that resilience requires a coordinated approach. Mitigation strategies increasingly combine infrastructure hardening, enhanced monitoring and refined operational response procedures.

Design improvements focus on better drainage, subgrade stabilization and protecting critical electrical and signaling assets from water intrusion. Monitoring efforts increasingly incorporate environmental sensors, rail temperature prediction tools and emerging technologies such as fiber optic systems capable of detecting washouts, ground movement and other right-of-way hazards. Pilot deployments and testing, including trials conducted at the Transportation Technology Center in Pueblo, Colo., are helping agencies evaluate how these technologies perform under real-world conditions.

Operationally, agencies are refining procedures for inspections, slow orders, shutdowns and recovery to ensure responses are timely, consistent and informed by data rather than assumptions. Research continues to play an important role in improving understanding of weather-driven failure mechanisms. Studies into frozen ballast behavior and rail break mechanics, for example, are helping refine maintenance strategies and rail adjustment practices for extreme cold.

Building long-term resilience

Extreme weather is now a permanent factor in rail transit operations. While it cannot be eliminated, its impact can be managed through informed design, adaptive procedures and strategic use of monitoring and testing tools.

The most resilient transit systems are those that:

- Recognize weather risk as a system-wide challenge.

- Invest in monitoring and prediction, not just repair.

- Continuously refining procedures based on data and experience.

As climate patterns continue to evolve, resilience will not be achieved through a single project or technology. It will be built incrementally through informed decisions, smart design and a commitment to learning from every extreme event.

About the Author

Radim Bruzek

Research & Development Program Manager, Transportation Technology Center

Radim Bruzek is currently a research and development (R&D) program manager at the Transportation Technology Center in Pueblo, Colo., operated by ENSCO, Inc. He oversees the all the R&D and engineering activities at the test center, including track and structures, rolling stock, signaling and human factors. Bruzek has been with ENSCO since 2011. He holds a Bachelor of Science and master’s of science degree in civil and structural engineering.