The Federal Transit Administration encourages the inclusion of art in transit systems by stating, “The visual quality of the nation’s mass transit systems has a profound impact on transit patrons and the community at large. Good design and art can improve the appearance and safety of a facility, give vibrancy to its public spaces and make patrons feel welcome.” It further attests to this point by providing funds toward art in transit capital projects.

As David Allen, director of Metro Arts in Transit for St. Louis Metro says, “It’s really pretty much a given now that there’s going to be an art component in any new system or alignment.”

How it started in St. Louis was how it has started at many agencies. “It started with a group of citizen activists who wanted artists to be involved in the design of the original light rail system,” he explains. “This goes back to the late '80s; it was rather groundbreaking.

“St. Louis Metro had a team of artists working elbow-to-elbow with the engineers and architects on the project, which was quite unusual for such a large infrastructure project at the time. As a result, a number of the key signature architectural features of our system were heavily influenced by the ideas and sensibilities of the artists from there.”

Allen adds, “Originally this was kind of an ad hoc group of citizens that were kind of driving this and eventually it got folded into Metro itself. Today it’s a fully supported program of Metro and we’re housed in the engineering division of Metro.”

Elizabeth Mintz, director of Communications for Southeastern Pennsylvania Transportation Authority (SEPTA) and the project manager for the authority’s Art in Transit program, says the program’s establishment grew out of a belief that aesthetic enhancement at stations and facilities can be an integral component of broader community outreach and partnership building efforts, undertaken in conjunction with capitally funded construction and reconstruction projects.

“We strongly support FTA’s core principle that the visual aesthetic of a transit system — specifically art — can have a significant and positive impact on customers and surrounding communities, says Mintz. “In keeping with FTA Circular 9400.1 (1995) and based on scope of the authority’s Capital Development program for station improvements and construction, the current Art in Transit program was established in 1998.” She adds, “SEPTA had installed art at a selected number of transit stations but not as part of a formal program.”

“SEPTA’s stations, terminals and headhouses are visible community landmarks,” Mintz says. “Using permanent art installations as a focal point, the authority seeks to strengthen its identity as a provider of public transit service and create an enhanced sense of pride and ownership for riders and the neighborhood surrounding a station.”

Making a Community

Brad Oldham, sculptor with Brad Oldham International Inc., explains the special needs of transit art. “One of the things about mass transit that I think is very important in the art world is that the artwork is approachable, that people can access it.” You don’t want it to be like a museum where people can’t interact with it, he says.

He adds, “Whether you invite them to or not, they are going to touch it.” In creating The Traveling Man, Oldham explains, “That’s a big part of why we used reflective materials in some of the materials so you morphed into the piece as you came up on it, almost like a mirror.” He stresses, “I think that’s real key because if you don’t feel like you can interact with the piece of artwork especially in that arena, the exterior world, it’s part of the public.”

Talking about the collaboration between Duo-Gard Industries and artist Vara Kamin for the art panels in shelters, Michael Arvidson, executive vice president for Duo-Gard Industries reflects what the FTA states. “Transit can be a stressful location for people. They’re coming to a spot, they don’t know the other people there, it could be dark, it could be in a not-so-great neighborhood or someplace they’re not familiar with, so it’s a way to provide a location that’s more pleasing and calming.” He adds, “They are something that’s not only beautiful, but they are proven to have a calming effect on people.”

Programs Providing Art

Agencies are incorporating a variety of arts in a variety of ways throughout their systems. A sampling of project ideas is shared here.

Allen from Metro describes Poetry in Motion, an annual regional competition highlighting chosen poems in posters for the trains and buses. “People can submit up to three poems and we select a panel of literary experts to judge the poems.” He shares, “Typically we have anywhere from 100 to 150 people submit the poems and we’ll usually get well over 300 poems.

“We select 15, we design them into posters and put them up in our trains and buses for a year and that’s accompanied with a poetry reading. The 15 are invited to come and read their poems to an audience of about 50 people.”

Metro Arts in Transit’s Art Bus Fleet consists of four to six buses where artists are commissioned to work with community sponsors and organizations, such as Boys and Girls Club, Big Brothers, Big Sisters, the Botanical Garden and other non-profit organizations that want to do an event. Allen says, “The artist will design the bus to coincide with the mission or the purpose of the organization and then we’ll bring it out at a weekend event where the sponsor organizes families and the bus is painted out in the community as an event.”

Both Metro Arts in Transit and SEPTA’s Art in Transit Program commission artists to create permanent works of art in public facilities. SEPTA has completed 17 projects, two selected projects are going through the internal review process, one Call for Artists is currently posted on its Web site and there are three additional projects in various stages of design development that will advance with permanent art installations.

Incorporating art in a less time-consuming process is offered by some suppliers, such as Duo-Gard with its art-enhanced shelters. “We started a year and a half ago working with Vara Kamin, who is an artist,” explains Arvidson. “We had talked to her regarding some architectural applications that our company is also involved in and felt that the philosophy behind her artwork was a good fit for transit so we have developed a program for including her different artwork into the variety of structures.

“We’re attempting to take art work to a larger scale of application to maybe a whole series or a whole city and one thing we have proposed to a couple agencies that are very interested, is to do an original artwork piece that represents their community and their identity.”

Making it Happen

Though incorporating art can increase costs, there are grant sources available to help with this that agencies talk about. Mintz says the SEPTA program draws from the FTA’s guidelines for Design and Art in Transit Projects and the city of Philadelphia’s Percent for Art Program allocates up to 1 percent of project costs for capitally funded projects for permanent art.

“I apply for a bunch of grants, state and regional and even federal money,” Allen explains regarding funding Metro’s Art in Transit. Those include National Endowment for the Arts grants, Missouri Arts Council grants and Regional Arts Commission grants.

The Call for Artist process solicits artist participation for a project, listing the type of artwork, the location and the schedule for completion of work. Mintz explains, for SEPTA’s process, “Before the Call for Artists is prepared, a meeting is held with the Art in Transit program manager, the Art in Transit program consultant, and the project architect and engineers to review the design drawings and identify the range of art opportunities. The final art selection is identified in the call, along with details about the project.”

She adds that with SEPTA’s sustainability program, an electronic Call for Artists is posted on the SEPTA Web site and electronic postings are sent to area art institutions and organizations, as opposed to paper calls being sent out to thousands of artists when the program initially began.

“The five finalists participate in an orientation session where they meet the design/engineering team and SEPTA’s community relations staff,” Mintz explains. “They get a detailed overview of the project, the constraints and opportunities of the locations selected for the placement of art and the project schedule and deadlines.” She says the presentation is followed by a question-and-answer period and a site visit with the project team.

For SEPTA’s program, the jury selection panel is comprised of five voting members and convened for each art project. The Art in Transit program manager is the only permanent member on the panel; the remaining four are selected to include a community representative, an artist who lives and works in or near the area surrounding the station, an arts professional, and an architect or engineer. The jury selection process is supported by a team of non-voting advisors, including the project architect/engineers and SEPTA community relations staff.

“The jury meets twice, the first time to review all complete submissions received. At the end of the first session, five finalists are selected who are invited to prepare a formal design proposal,” says Mintz. “The second time the jury meets they see the final proposals and recommend a first place artist and project.

“To facilitate the artists’ creative process and to develop an aesthetic for the renovation that speaks from the voice of the neighbors, input from the community is sought,” Mintz explains. “At a workshop-type meeting, the community is asked to articulate qualities and characteristics that define the surrounding neighborhood and identify events, individuals, landmarks and features that make their community unique.

“This meeting is held while the artists are preparing their final design proposals and they are invited to attend the meeting, listen and ask questions.” She adds, “SEPTA strongly encourages the finalist artists to do more than take the information from the community meeting, we ask them to go into the community — talk to the people — to help develop their creative ideas.”

Arvidson says something he’s been seeing more of is that agencies are going to more of a proposal format. “They’re asking companies to provide a proposal on how they can satisfy the agency’s needs so you can sometimes bring a whole new concept to the table and then the agency will choose which concept they like better or which materials they like better.” He says, “It gives more flexibility in ending up with a product that might fit the goals of the community, therefore art can be included easier that way.

“If you put out a bid that says we want 10 brown box shelters, you have to take the lowest bidder. For a proposal, you have many other factors that are decision-makers besides the lowest price.”

For one agency Arvidson works with, it worked with a lot of local artists for each location and it was cumbersome and very time-consuming. “When you’re dealing with a number of different vendors that aren’t used to dealing with this type of production works, it becomes very difficult to manage.”

Mintz talks about working with artists and what SEPTA has done to improve the process. “Public art is very different from the studio art process,” she stresses. “Artists who successfully compete and win public commissions must possess creative skills and ability as well as strong business skills and be familiar with the requirements and rigors of a public construction project.

“Making the transition from creating in a studio to art as a business can be daunting for many artists, which often limits the number of submissions received through an open call process,” she says. “To help bridge this gap and encourage more artists to venture into the public art realm, SEPTA held two Art in Transit workshops for the Market Street Elevated Reconstruction.”

This project reconstructed six stations along one of SEPTA’s busiest transit lines and each station had an art component. Regional and neighborhood artists were invited to learn more about the public art process, SEPTA’s Art in Transit Program, practical tips on submitting credentials for the call, creating a final design presentation and how to establish a budget.

Oldham advises agencies to ensure the artist understands construction. Oftentimes artists are independent and their work is very important to them, how it gets portrayed is important, how it gets built is typically not their most important thought. “It’s the end result that is very important and it takes educating an artist to be able to have a successful collaboration.”

Creating a Smooth Process

From the artist’s perspective, Oldham shares that things have been similar with the many different agencies he’s worked with, especially regarding the paperwork and the meticulous attention one has to pay to it.

“The thing that made it easiest to work with was giving us access to all departments,” he says of working with DART for The Traveling Man. “There is usually one lead, one project manager that is your go-to guy that you have to submit all your paperwork to, but with DART in particular, they gave us access to their contacts at the city and then the contacts within DART.” He emphasizes that weekly and biweekly meetings to connect with all of these people helped ensure everyone understood what was going on; everyone was on the same page. “There is so much work to be done that you can’t go through one person; that’s just not possible.”

“Public programs have to be vigilant to make sure that the purpose of why we do what we do is understood by the general public because we really depend on the public support to continue in operation,” Allen says. Because of their procurement process to comply with FTA regulations, he explains they have to be diligent about the way they go about purchasing anything, whether that’s the consultants, artists or materials. He adds, “But that’s not really that much more cumbersome than any other government agency or municipal agency.”

With panels and juries selecting art, running into problems where art was considered offensive or overly provocative has not been an issue. “There’s a fine line, but the way that most programs are similar to panels, it includes people that really kind of get it in terms of working in the public realm and it is a different forum than working in a private gallery — a private space vs. a public space.”

Mintz voices a similar sentiment. “Because SEPTA places great emphasis on community participation and voice, the community representative and local arts professionals who sit on the jury selection panel play a very important role in the selection process. They are encouraged to express how they think the broader community will feel about a particular design concept.”

Growing a Program

“The fact of the matter is, it seldom starts within the agency itself,” Allen says of art in transit programs. When he ran an art program in Southern California, he had an artist under contract from Minneapolis and the artist told of meetings he had been attending. “These community meetings, people were insisting that there had to be art designed into the system and that’s where it came from,” Mintz says. “The community insisted. For anybody that was interested, form a grassroots group.”

Of his experience of working on The Traveling Man, Oldham says, “It not only builds DART’s or the transit line’s marketing and power, it really helps bring a community together.

“First thing we did was to go to five or six different little shops right around our area and start introducing ourselves, start knowing those people and they started coming out and we were always very accommodating, taking photographs and giving people information. You saw the same people coming out every Thursday night, taking pictures.” He stresses, “It really makes you feel like you were part of the neighborhood.”

Traveling in Deep Ellum

The Traveling Man is a $1.4 million sculptural series designed by Brad Oldham, Brandon Oldenburg and Reel FX Creative Studios near the DART Deep Ellum Rail Station. The Traveling Man consists of three different sculptures on three distinct sites along Good Latimer Avenue.

The Traveling Man Walking Tall is a 38-foot sculpture on the northeast side of the station. Described as “on the move with a happy stride,” he is accompanied by four bird friends the artists incorporated to add an approachable scale to the sculpture. The 42-inch-tall sculptures are cast in stainless steel and polished to a mirror finish and the scooped backs create a perfect place for visitors to perch.

The Traveling Man Waiting on a Train is a 9-foot-tall structure at the southwest corner of Good Latimer and Gaston Avenues depicts The Traveling Man leaning against a concrete artifact, waiting on a train, and strumming his guitar with the bird friends nearby. He is described as having a “Huck Finn” quality that invites people to join him.

A 1,000-square-foot space near the corner of Good Latimer and Elm Street is the home of The Traveling Man Awakening, a 4 1/2-foot sculpture. The Traveling Man’s head is coming up from the ground, as if waking from the Earth. The bird friends are nearby as The Traveling Man is sleeping, but nearly awake.

Each sculpture tells a story, incorporating many aspects highlighting the community, particularly the musical background and industrial roots. The materials used in The Traveling Man are metals commonly used in the industries of this neighborhood and to add a reflective quality to draw the viewer in.

For more information, visit www.bradoldham.com.

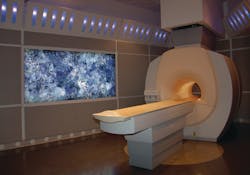

Creating Intentional Space: Peace in Public Places

Duo-Gard and artist Vara Kamin, founder/president/artistic director of Impressions of Light Inc., have collaborated to create a new concept for public transit shelters and stations. The shelters incorporate the artist’s work of illuminated art panels for ceilings and walls. Kamin’s art was originally used in hospitals and healing centers throughout the United States to help in decreasing anxiety in high-stress environments. Her images provide a visual respite and a positive point of focus. In this sensory art, viewers become engaged in creating personal meaning from what they see.

“In the transportation industry, perhaps the placement of these unique images in shelters and stations could not only enhance rider experience, but also potentially contribute to a sense of community by supporting a new level of respect for shared public space,” Kamin told Duo-Gard.

The sensory art panels in the shelters contribute to a sense of community, reduce passenger stress, create positive rider perception, shape passenger experience, support respect for shared space and engage riders with special visual focus.

For more information, visit www.duo-gard.com to see Sensory Panels.

St. Louis Art in Transit

Current projects at Metro include a variety of 2D art. AIT issued a call for 2D public art proposals, open to artists within 100 miles of St. Louis.

AIT received more than 95 proposals and selected the following artists: Jon Cournoyer, Deanna Dikeman, DB Dowd, Cary Horton, August Jennewein and Susan Pittman. Selections were made by a panel of judges consisting of artists, arts professionals and a member of the AIT Advisory Council. Selections were based on “visual and conceptual excellence and the ability to impact metro riders and the general public in a positive fashion.”

For more information, visit www.artsintransit.org.

Art in Transit at SEPTA

Creating a more inviting and dynamic transit environment for riders, the Arts in Transit program at SEPTA allocates up to 1 percent of its construction budget of capitally funded projects for the design, fabrication and installation of permanent artwork.

Artists living in the Greater Philadelphia area are invited to apply for public art commissions for the program that fosters a feeling of pride within the surrounding community.

SEPTA currently has two projects in the review process and a call for artist for another project. It currently has 17 other installments along its lines and at its stations.

For more information visit www.septa.org.