Squat-type Defect Remediation on Sound Transit and the Search for Effective Preventive Maintenance Measures

One of the most vexing and increasingly common rail defects that rail transit agencies contend with is the squat-type defect (stud). Addressing studs has been challenging in that they are not fully understood, and while contributing factors are known, the exact root cause(s) are not definitive.

“Identifying and classifying the cause of rail damage is the first step in executing an effective prevention or remediation program,” Mark Reimer, director and co-founder of Sahaya Consulting, told attendees at the 2025 Wheel/Rail Interaction Rail Transit conference, of which Mass Transit magazine is the presenting sponsor.

Reimer and Sahaya Consulting’s experience at Sound Transit, where rapidly forming studs have been the focus of maintenance efforts for many years, have helped build a better understanding of studs and stud remediation. However, questions about how to prevent them in the first place remain.

Many incipient rail defects can be controlled by regular preventive grinding. As defects grow deeper, remediating them requires significantly more effort. According to Reimer, studs are problematic because they are known to develop quickly (within 10 MGT), and by the time they are visible, they are generally quite large subsurface defects—too deep to remove through a typical maintenance-grinding program. Figure 1 shows an example of a stud pre- and post-grinding. When multiple studs occur in close proximity, it’s common for the defects to link up beneath the rail surface and cause large pieces of material to spall out.

Figure 2 summarizes some of the known characteristics of both squats and studs. Reimer notes the primary distinction is that studs can develop within 10 MGT and, unlike squats, there is little, if any, evidence that studs can develop into a transverse defect or broken rail.

“There doesn’t appear to be the same critical safety implications with studs,” Reimer said, while noting that rail breaks have occurred at or near studs, but there is no evidence that the breaks occurred because of the stud.

Based on data from multiple studies and multiple transit agencies, Reimer explains studs are known to have the following characteristics:

- There is little to no plastic deformation.

- They can form very quickly, within 10 MGT or less.

- They have been found in both new and old rail, on tangents and in curves.

- They always form in the presence of white-etching layers (WELs), a martensitic layer which is very hard and brittle—evidence of a thermal change such as a wheel slip or grinding activity (See Figure 3).

- They do not appear to form in tunnels.

There are several contributing factors that appear to be related to stud development. One is the use of premium heat-treated rail steels.

“Light transit systems don’t see the same level of wear as freight railroads do, so the white-etching layers that form aren’t worn away quickly,” Reimer said.

This may also be why studs don’t seem to form in tunnels, where the drier environment leads to higher rail wear rates and more consistent friction levels.

Traction effort has also long been thought to be a contributing factor in stud formation. The switch from DC to AC traction, and the addition of multiple driven axles that has occurred over approximately the last 30 years, coincides with the appearance of studs on many transit systems.

“The significant increase in tractive effort over the last 30 years may be a contributor, but we’ve also seen studs on systems with older DC traction and on systems with linear induction motor systems,” Reimer said.

Another theory is that studs may be initiated by wheel slips on work vehicles, rather than revenue service fleets; however, there is no conclusive evidence at this time.

Studs on Sound Transit

When studs first began to appear on Sound Transit’s system, the primary concern was that they were squats that posed a significant risk of a rail break. However, Reimer notes data from analyses conducted at Sound Transit and from previously published studies convinced all involved that these defects were studs and not squats, and that they posed less risk of a rail break. Figure 4 shows a figure from one such study which highlights the way the defect propagates horizontally and comparatively shallowly, rather than vertically though the rail (vertical propagation is often associated with rail break risk).

“Instead of turning downward into the rail, most of the cracks we’ve sectioned start to migrate back to the surface,” Reimer said.

Studs first appeared in great number at Sound Transit on a tangent track with co-occurring corrugation. Reimer says Sound Transit first approached the problem by remediating the studs in small batches.

“They initially did some rail head weld repairs—when the studs were thought to be classical shelling— then moved on to rail grinding, rail milling and finally rail renewal programs to remove the studs,” Reimer said.

Part of the remediation work has been to build a better understanding of studs and determine how to prevent them before they occur or remediate them very early in their development. Sound Transit has since phased out rail head weld repairs, as some of these repairs have led to rail breaks in conjunction with stud defects.

“We haven’t seen a stud develop into a rail break, but that doesn’t mean that rail breaks never happen around them; only that the stud itself is more a maintenance issue than a safety issue as long as it’s not combined with other track defects.” Reimer said.

There is one particularly stud-affected five-mile stretch of track where Sound Transit has done significant remediation work—although studs appear elsewhere on their system.

“Initially, Sound Transit considered that this stretch might be the result of defective rail,” Reimer said.

However, as work continued, studs were found in all types and ages of rail used in the area. Additionally, tests of stud-affected rails showed no inherent metallurgical defects, disproving the “bad rail” hypothesis, Reimer explains. As the affected rail has been replaced over time, studs have continued to appear, though lesser in number and severity. Nonetheless, Sound Transit has continued to replace many of the most severely affected rail sections.

As Sound Transit worked to remove the studs, even at the incipient level rail grinding proved to be inefficient on the system.

“Through rail grinding, we exposed the subsurface cracks of the studs but didn’t get to the bottom of them,” Reimer said.

Removing these studs required multiple passes of a rail milling machine, reaching depths of 4 millimeters (0.16 inch) to 8 millimeters (0.31 inch)—an amount of metal removal that Reimer notes is uneconomical for small transit grinders.

Since the rail was milled, it has accumulated 30+ MGT, and there are few signs of studs redeveloping. The milled and replaced track sections have also been ground regularly, beginning in 2018, which likely contributes to the lower incidence of studs.

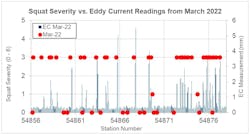

According to Reimer, as part of these preventive grinding efforts, consultants have used eddy current and ultrasonic technology to help “identify, characterize and map out stud locations.”

Figure 5 shows an example of measured stud severity (the blue bars) versus a visual inspection of severity estimate (red dots).

“The problem with studs is that they don’t always look as severe as they are until you start cutting into them,” Reimer said. “We’ve had mixed results using both eddy current and ultrasonic technology to map out stud severity, so this is a work in progress.”

He notes that it’s even more difficult for these technologies to measure stud severity in their incipient stage, so visual inspection is still an important part of the toolkit.

Despite the remediation and preventive grinding programs Sound Transit has put in place, studs remain a persistent problem.

“We’re pretty confident that the presence of WELs is a key indicator of the root cause, but we don’t know how to measure the thickness or depth of WELs in situ, or at what depth or thickness it might initiate a stud,” Reimer said.

Sound Transit has implemented friction management in the form of gage-face lubrication to address noise concerns, but Reimer notes that the addition of top-of-rail friction modifiers could potentially help control wheel-slip events and thus reduce stud formation as well.

While progress has been made in remediating and slowing their development, their exact root cause remains unknown. The understanding of squat-type defects has evolved and continues to evolve. With studs becoming more common on transit systems around the world, this understanding is sorely needed. Still, knowledge gaps remain on how to prevent stud formation, rather than simply remediating them.

“Prevention is always preferable to remediation,” Reimer said.

The industry is working on it.

This article is based on a presentation made at the 2025 Wheel/Rail Interaction Rail Transit Conference. https://wheel-rail-seminars.com/

About the Author

Jeff Tuzik

Jeff Tuzik is managing editor of Interface Journal. His work appears through an agreement with Wheel/Rail Seminars of which Mass Transit is the presenting sponsor.