“Nobody cheers for an acronym,” said Dr. Bob Schneider on why his transit agency, The Comet, just got its third name in a little over a decade. He cited the flagship state university, one of the bigger trip generators in Columbia. “People here love USC, but they cheer for the Gamecocks. We didn’t want to be just another abbreviation,” such as the previous name, the CMRTA, for Central Midlands Regional Transit Authority. “You would not believe how many ways there are to mispronounce that,” he noted.

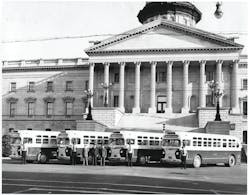

The Comet has had one of the stranger trajectories in the transit business. It was still a privately held property until 2002 by which time all other American transit agencies had gone public, usually in the 1960s and 1970s. The agency has had three names and four owners in just over a decade, had two tax referendums in the last two election cycles, survived a state supreme court challenge in the last year, and nine of 11 employees are new hires, including Schneider even though he has been running transit in Columbia for three years now. Oh, and in 2012 the agency cut 40 percent of its service. “Needless to say,” Schneider noted, “there has been an adjustment period.”

This Comet has a very long tail. Thanks to the Broad River Power Case of 1929 the attorney general of South Carolina had compelled the power company to operate transit in Columbia. In 1930, the United States Supreme Court upheld the decision stating, “the privilege of operating the street railway is inseparable from that of operating the electric power and light system, and that together they constitute a unified franchise.” The U.S. Congress had other ideas, however, and in 1935 passed the Public Utility Holding Company Act, commonly known as the Divestiture Act, which required electric utilities to shed their non-utility operations including vast fleets of streetcars in transit service around the country.

The electric companies needed little prompting; by the 1930s the streetcar era in American had ended and transit was a money loser (the only mention of the Columbia railway in the Broad River Power Company 1928 annual report was under liabilities on the balance sheet). In the midst of the Great Depression electric utilities were all too happy to be rid of such a white elephant. It is worth recalling the Presidents Conference Committee, a collective of streetcar executives from around North America, first met in 1929 in an effort to stem the tide of transit ridership decline. The eponymous PCC cars — fast, smooth, and gorgeous — only delayed the inevitable decline and the Divestiture Act certainly helped speed things up.

Nationally there were still several electric companies operating transit into the late 1970s including those in St. Joseph, Missouri, New Orleans, and Charleston and Columbia, South Carolina. Because the Divestiture Act was a federal law only power companies crossing state lines were compelled (or allowed, as the case may be) to comply and thus Broad River and its successor the South Carolina Electric & Gas Co. ran transit in Columbia and its environs for nearly 80 years (although streetcar service was discontinued in 1936). But everything comes to an end, especially privately operated American transit agencies and SCE&G’s acquisition of the Public Service Company of North Carolina Inc. in 1999 finally opened the door to divesting transit from power in Columbia.

In December 2001 news broke that the city of Columbia would take over transit in the city and in 2002 the Columbia City Council entered into a conveyance agreement with SCE&G, releasing the power company from any and all obligations to run the transit system and passing the function on first to the city and then to the fledgling CMRTA. Transit is in the expense column for municipalities, which begs the question of why the city of Columbia was willing to take it on in the first place. While city leaders certainly wanted better transit than a utility company was inclined to provide, an attorney familiar with the proceedings noted that in addition to the transit part, the agreement yielded a hydroelectric power plant for the city, which then sold the electricity back to SCE&G.

Columbia sits on the confluence of the Broad, Saluda and Congaree Rivers, and like the water system in the city, events were converging to press the transit issue. The CMRTA ran on a potpourri of funding sources including the city of Columbia, Richland County, federal and state dollars, and the continued contributions of SCE&G on a schedule of decreasing amounts ending in October 2009. The need for a permanent funding plan was clear. In 2008 Richland County commissioned a transportation study but then voted not to include a transportation-funding question on the November ballot. The SCE&G money was running out and it was 2008 (yes, that 2008), which bled into 2009, and Columbia was feeling the recession. In 2010 the Richland County Council revisited the transportation tax and this time voted to place a 1-cent sales tax referendum (hereafter, the penny) on the November ballot. It failed by only 2,200 votes.

Schneider came to Columbia by way of Knoxville where he earned his PhD in political science at the University of Tennessee while serving as the chief operating officer for Knoxville Area Transit, and then Boise, Idaho, where he was the general manager for Veolia at ValleyRide. In November 2011 Veolia offered him the same position in Columbia and he jumped at the chance. The CMRTA was facing dire financial circumstances and in May of 2012, the agency imposed what could only be called Draconian service cuts to staunch the budgetary bleed. Routes were eliminated or merged with others to form giant loops, and headways were stretched to get to that 40 percent figure mentioned above.

As both the general manager (employed by Veolia) and executive director (employed technically by the RTA board, although Veolia had agreed to allow him to take that position without salary), Schneider had short- and long-term needs for a predictable, dedicated funding source. The penny was essential to the survival of the transit system of which he was both employee and director and the penny tax became his highest priority. He worked with the Chamber of Commerce, Citizens for Greater Midlands, and most importantly Richland County Government to develop a successful $1.07 billion transportation sales tax referendum question, which would generate more than $300 million dedicated to The Comet over the next 22 years if it passed.

In the 2010 election a long-time transit board member actually came out against the penny, but that was only the most cosmetic problem supporters had faced. Heyward Bannister heads a Columbia-based public relations and political consulting firm and ran the political campaigns for the penny tax in 2010 and 2012. He said there were four essential lessons of these two elections and these are relevant to cities and transit properties across the United States. The first is turnout. The higher the office, the higher level of voter participation and 2010 was a gubernatorial and congressional election; 2012 was a presidential and more people show up. Second, although transit was the catalyst for the penny transportation tax, there had to be something else. County leaders, “figured if it was just for transit it would not pass. There had to be roads, sidewalks, greenways,” too, Bannister said. Third, “we got whipped in the absentee voting process. We were whipped 2-to-1,” so in 2012 they got mailings out early to make sure they had information in voters’ hands before they mailed in their ballots.

The fourth lesson was perhaps the most critical: losing the first time helped. “We were saying in 2010, if this tax does not pass, funding for the transit system will either no longer exist or it will be cut substantially and there will not be long-term sustainable revenues.” People would not be able to get to work, Bannister explained to voters. People would not be able to get to medial appointments and weekend services would be eliminated. “And what we were talking about happened, and then people said ‘it was real.’” On November 6 the penny passed. On November 29 RTA staff were already planning to restore services cut during the crisis.

Not long after the confetti was swept off the floor, however, the hard won penny sales tax was in jeopardy. Michael Letts, a local activist for more accountable government filed a lawsuit in late 2012, arguing that long lines and too few poll workers discouraged voters and lead to widespread disenfranchisement. The challenge went all the way to the state supreme court, but voters had approved the tax by a 9,345-vote margin, and in a concise, 160-word order, the state supreme court voted unanimously in March 2013 to dismiss the case. The voters have spoken, let’s get on with it they seemed to say. Schneider was finally able to hire staff to begin implementing his vision for transit in Columbia. But first things first: at the next meeting after the supreme court decision the RTA board voted to change the agency’s name to The Comet.

Schneider ended his employment with Veolia in July 2013 when the authority board voted to make him the executive director of the agency on a full-time, salaried basis; that same month he brought in the first new employees to The Comet. In August the Gamecock Express was debuted in partnership with the University of South Carolina, generating more than 10,000 trips in one day; a new rural pilot service was developed and launched in January 2014 that expanded flex-service into the rural portions of Richland County and connects to three separate fixed routes; spring service improvements will include restoration of key Sunday routes and improvements in route frequencies on several weekday routes; The Comet is in the process of ordering bus shelters, benches, bike racks, bollards, and grocery cart racks branded with The Comet icon, the very first stop amenities the agency has ever procured.

The icon is central to The Comet’s brand, a reborn transit agency that is “designed to be infinitely more accessible to the entire community and something the community can be proud of,” Schneider said. “We want something people will like to ride rather than what people have to ride. We have an icon we want the community to identify and that our customers will be proud to be part of.” And that is something the greater Midlands can cheer for.